Further to Tuesday night's report on the Wilberforce Address, here is the speech given by Rev Katie Kirby of the African and Caribbean Evangelical Alliance. The official version of David Cameron's can be found at the Conservative Party website.

The pain, problems and potential of the legacies of the slave trade

In the year that we mark the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade, I made my first visit to an African country. Malawi, which is known as the warm heart of Africa, welcomed me in a way that I found deeply connecting and deeply disturbing at the same time. Connecting, because of the similarities in food, body language and expression, and my instant adaptation to the warmer climate. Disturbing because in between the natural beauty and pockets of prosperity were clear signs of acute poverty and deprivation. It was in talking to local people and hearing their concerns and aspirations for their country and its people, that it became clear that some of those visible signs of deprivation had their roots in the mindsets that had been handed down through generations resulting in a legacy for some of poverty, a legacy which the government and churches are working to address.

In preparing to speak to you this evening, I came across a range of books, articles, official and unofficial websites, blogs and pod-casts dedicated to exploring the impact of the slave trade. While each author and contributor had their emphasis, tone and focus of their information, none left me in any doubt as to what slavery was – and indeed is.

Across the range of information, two common threads emerged. The first is that the footprints of the deplorable and systematic enslavement of human beings have been left across every country, continent, and culture. Where enforced, slavery devalues human life without exception and people become property. Where endorsed, slavery is seen a measure of economic strength or a means of political persuasion. The second and perhaps the more challenging thread, is the role that the church and the Christian community played in both the advancement and the abolition of slavery. What is clear is that both threads both have left legacies.

A legacy is defined as a bequest made in a will, something from the past, and something outdated or discontinued. And so 200 years after the British Parliament said ‘no’ to the slave trade, its important to ask ourselves the questions, what has been bequeathed or left from the past? What has been inherited and by whom? And does it remain relevant or should it be discontinued? The legacies of the slave trade are many and could keep a research fellow occupied for longer than I the time I have with you this evening. So I have grouped legacies of the slavery into three areas: the pains of the past, the problems of the present, and the potential of the prophetic (or the future).

The pain of the past

Dr Joy De Gruy Leary says that ‘we must return and claim our past in order to move toward our future’. Many who have traced their history and heritage have found that looking back means acknowledging events and information that are painful to process, and in some cases, difficult to disseminate. Coming face to face with the knowledge that our past includes your ancestors either being robbed of their identity, value and dignity, or that our ancestors were perpetrators of these atrocities opens up a plethora of challenging emotions and experiences that some have found difficult to process or channel while others have been confident enough to channel them into something beneficial. The question we each need to ask ourselves is: what in our history contributed to the pains of the past?

The problems of the present

The second broad group of legacies are issues those that manifest themselves in superior or inferior behaviour within or between people groups. These are problems of the present that show up as disrespect for human life, a disregard for authority, a disparagement of identity, and in a growing number of cases the disdain of a belief and faith.

Slavery blurred and indeed destroyed lines of heritage and lineage for those people groups who it was forced upon, deconstructing what many believe to be the foundation of a stable community and society – the family – a process that is still occurring today.

Slavery displaced Africans across the Americas, the Caribbean and Europe and despite abolition, the aftermath of slavery continues in various expressions of segregation, inequality and racism. Individual and institutional racism have been cited as the catalyst in a myriad of violent and often criminal actions which have made the headlines locally, nationally and internationally. Martin Luther King said that 11am on a Sunday morning is the most segregated hour in America, a statement that despite being a multi-cultural society, still seems to ring true here in the UK.

The gaps in educational achievement indicate the continuing disparity of access in learning, and the over-representation of Black people groups in mental health institutions and the criminal justice system clearly reveals the mindset towards those considered less able because of their background and heritage. The question we each need to ask ourselves is what in our history contributes to the problems of the present?

The potential of the prophetic

Before, during and since abolition, many voices have championed the cause of the marginalised, the disenfranchised, and the displaced. In the 18th century, Olaudah Equaino was among those who spoke and wrote about the possibilities that a ‘free’ future could hold for his people and all people. In the 20th century it was Martin Luther King who spoke and wrote prophetically about the future, raising the hopes and aspirations of millions of African Americans. Later in the same century, Nelson Mandela could be heard championing the cause of the oppressed in the fight against apartheid in South Africa.

These three and others were bold enough to speak in their time, for their time and for the future, but not without risk or cost. The legacy that they have left was and is prophetic. The question we each need to ask ourselves is what in our history contributes to the potential of the prophetic?

Conclusion

To-date, we have heard from those who have expressed regret for the slave trade. Those expressions, although welcomed by some, were perceived by some as hollow because of the absence of an act of regret. We have also heard the calls for reparation which, if carried out like a refund from a high street store with a no-quibble policy, will simply reduce the rich and priceless heritage of the people, their personalities and potential ravaged by slavery to a monetary value.

In my view, an apology or expression of regret is insufficient if done in isolation, and there is no cheque that could be written to repair or replace valuable lives that were tragically and brutally lost because of slavery. A lasting legacy would be an act of repentance and reconciliation – a visible and tangible act through which the our churches, communities, agencies, businesses and governments demonstrate a lasting commitment to the reality of abolition by investing in the present and future of those disenfranchised by the negative legacies of the slave trade.

The footprints left by slavery cannot be ignored or indeed forgotten. In fact on the contrary, this painful and problematic era of our history needs to be told, and retold accurately, so that history is the right story. I call on Africans and Caribbeans to record our story, acknowledging our part in the slave trade and the legacies it has left. In doing this, I believe that we will not only learn from the mistakes of the past, but play our part in leaving a legacy of knowledge will better serve the heritage of those who have risen out of slavery. It will also ensure that the legacies that currently appear negative can be appropriately recognised, and better understood.

Martin Luther King said: I have a dream. I say, I have an expectation, an expectation that one day the legacies we rehearse about the slave trade, will lead to the legacies of abolition which include an honest recognition of the pain of the past, a willingness to address the problems of the present, and a strong desire to see (hear) the potential of the prophetic. I also believe that if we want to be, each of us can be part of the answer to Jesus’ prayer for unity in John 17:21, and play our part in the restoration of identity, of value and of dignity to human life right across every custom, culture, country and continent.

Further to my Tuesday post on proceedings of the United Nations Human Rights Council, which have now concluded, UN Watch has expressed its disappointment over the Council's failure to address the vast majority of human rights abuses occurring around the world.

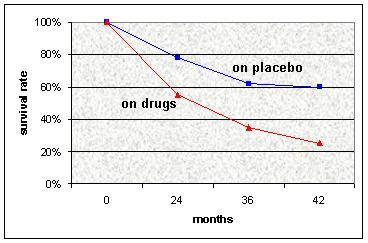

Further to my Tuesday post on proceedings of the United Nations Human Rights Council, which have now concluded, UN Watch has expressed its disappointment over the Council's failure to address the vast majority of human rights abuses occurring around the world. Although 700,000 people are affected by dementia in the UK, only £11 is spent on UK research into Alzheimer's for every person affected by the disease, compared to £289 for cancer patients.

Although 700,000 people are affected by dementia in the UK, only £11 is spent on UK research into Alzheimer's for every person affected by the disease, compared to £289 for cancer patients.

In the current edition of

In the current edition of  Zimbabwe's opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai

Zimbabwe's opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai  George Carey, former Archbishop of Canterbury, speculates in today's

George Carey, former Archbishop of Canterbury, speculates in today's  Given all that is going on in

Given all that is going on in  So, if you must lobby your MP, don't let them simply agree the world is unjust. Find out precisely what they intend on doing to make it a fairer place. Remember Michael Ancram's Zimbabwe visit to meet with opponents of Mugabe's regime? What exactly is your MP doing to promote freedom and opportunity for all across the world, not just in Britain? Buying the right coffee is no longer sufficient.

So, if you must lobby your MP, don't let them simply agree the world is unjust. Find out precisely what they intend on doing to make it a fairer place. Remember Michael Ancram's Zimbabwe visit to meet with opponents of Mugabe's regime? What exactly is your MP doing to promote freedom and opportunity for all across the world, not just in Britain? Buying the right coffee is no longer sufficient.

Since its creation on 25 March 1957, the European Union, together with NATO, has facilitated economic reconstruction and the consolidation of democracy across the continent, so it is right to mark this anniversary. However, like any other 50-year-old, Europe today finds itself asking some fundamental questions about its purpose and needs to look to the future, to rise to the challenges that David Cameron calls "the priorities of a 3G Europe": Globalisation, Global warming, and Global poverty.

Since its creation on 25 March 1957, the European Union, together with NATO, has facilitated economic reconstruction and the consolidation of democracy across the continent, so it is right to mark this anniversary. However, like any other 50-year-old, Europe today finds itself asking some fundamental questions about its purpose and needs to look to the future, to rise to the challenges that David Cameron calls "the priorities of a 3G Europe": Globalisation, Global warming, and Global poverty.

Just when you thought the issue of Islam was beginning to disappear from the news, a couple of headlines come along that seem to indicate some kind of sensible balance between tolerance and freedom is now being achieved:

Just when you thought the issue of Islam was beginning to disappear from the news, a couple of headlines come along that seem to indicate some kind of sensible balance between tolerance and freedom is now being achieved:

As we embark on the fifth year of the war in Iraq, I thought I would highlight the

As we embark on the fifth year of the war in Iraq, I thought I would highlight the

A couple of days after an appeals court in Egypt upheld the four-year jail sentence imposed on the blogger convicted of insulting Islam and President Mubarak (see

A couple of days after an appeals court in Egypt upheld the four-year jail sentence imposed on the blogger convicted of insulting Islam and President Mubarak (see  Today's

Today's